I adore superhero films, no question about it. A colleague of mine, author/blogger Sean P. Carlin, recently wrote an essay called “The Great Escape: What the Ascendancy of Comic-Book Culture Tells Us About Ourselves” where he eloquently lambasts the superhero tide flooding the movie industry and its effect on our culture. It’s a scholarly, well-structured argument backed by contrasting quotes from comic greats like Alan Moore and Grant Morrison. Sean suggests that reverence for these now corporate-fueled characters is causing societal ignorance of real world affairs while placing the film industry in a creative doldrums. Give the essay a read.

Done reading? Good, because I’m about to unleash my inner fanboy.

I was a huge Marvel fan long before their characters ever appeared on screen. The idea of Patrick Stewart playing Professor X was the pipedream of a doe-eyed child, not a reality. But I drifted away from comics…until Y: The Last Man sucked me back into the medium and the Avengers vs. X-Men storyline resurrected my love for superheroes. Since then, I’ve been amassing X-Men and Wonder Woman collections (amongst others), all of which contribute to my creative inspiration as a writer.

We are living in a golden age of superhero films. Due to rising ticket prices and my decent home theater setup, I typically only go out to see my favorite heroes. Why? The quality of filmmaking has become so impressive, and the characters continue to evolve. Of course, some superhero films are better than others (many suffer from third act and villain problems) but they continue to strive for greatness. The genre’s nature allows fans to take whatever they need from the experience, whether it’s escaping the pessimism of our world by reveling in the spectacle or connecting with a deeper subtext about modern issues.

Superhero films offer entertainment, community, and cultural reflection. In my opinion, there’s not a damn thing wrong with that. Now, Sean, the debate begins.

What is the Audience for Superheroes?

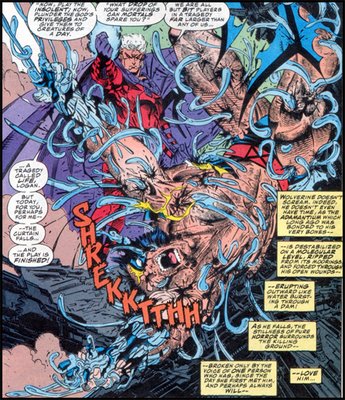

Sean laments the increasing trend of more mature superhero storylines, particularly in film, and feels that their focus should return to the 9-13 demographic. When was the last time comics were truly aimed at children? 1982 when Bullseye cut Elektra’s throat and impaled her? Or was it 1986 in The Dark Knight Returns with Joker’s murderous rampage through a carnival? Or perhaps 1991 when the relaunch of X-Men saw the adamantium ripped from Wolverine’s body? Then there’s 1992 when Superman was beaten to death and Image Comics launched ultra-graphic titles like Spawn where demons ripped out people’s still-beating hearts. That’s at least 35 years of storylines hardly suitable for young’uns.

Sean laments the increasing trend of more mature superhero storylines, particularly in film, and feels that their focus should return to the 9-13 demographic. When was the last time comics were truly aimed at children? 1982 when Bullseye cut Elektra’s throat and impaled her? Or was it 1986 in The Dark Knight Returns with Joker’s murderous rampage through a carnival? Or perhaps 1991 when the relaunch of X-Men saw the adamantium ripped from Wolverine’s body? Then there’s 1992 when Superman was beaten to death and Image Comics launched ultra-graphic titles like Spawn where demons ripped out people’s still-beating hearts. That’s at least 35 years of storylines hardly suitable for young’uns.

Comics were only truly kid-oriented many, many decades ago when the now-defunct Comics Code Authority was censoring content. Heroes and villains explained their powers aloud every time they were used, stories were simplified through overt exposition, and the dialogue was stiff. Comics were a product of their time, but the world has become more complicated. More gray. Stories have progressed into multi-issue arcs with far more subtlety and gravitas. But to say comics should pander to a specific age range belittles the art form and suggests kids aren’t able to appreciate more sophisticated storytelling. Should novels in the school syllabus like Catcher in the Rye be censored or made more “kid-friendly?” Hell, The Hunger Games is suggested for 11-13 yet revolves around children murdering each other.

Comics were only truly kid-oriented many, many decades ago when the now-defunct Comics Code Authority was censoring content. Heroes and villains explained their powers aloud every time they were used, stories were simplified through overt exposition, and the dialogue was stiff. Comics were a product of their time, but the world has become more complicated. More gray. Stories have progressed into multi-issue arcs with far more subtlety and gravitas. But to say comics should pander to a specific age range belittles the art form and suggests kids aren’t able to appreciate more sophisticated storytelling. Should novels in the school syllabus like Catcher in the Rye be censored or made more “kid-friendly?” Hell, The Hunger Games is suggested for 11-13 yet revolves around children murdering each other.

“Children plainly aren’t the audience Dawn of Justice is being marketed to or made for, any more than Deadpool or Suicide Squad or X-Men: Apocalypse or Jessica Jones are….and that’s problematic, because today’s youth aren’t going to discover—aren’t going to emotionally invest in—that which isn’t produced to specifically appeal to them, to stoke their receptive imaginations.”

Sean P. Carlin

The current slate of Marvel and DC films falls in the PG-13 range. While Marvel is a bit more whimsical in their content and DC a bit darker (as per tradition), the films are generally accessible to a younger age, even if some of the heavier themes elude them. However, the onus is on both companies to introduce their characters in an appropriate manner for all ages, and they’ve done exactly that. There are so many avenues for children to enjoy these characters––learning to read books, LEGO sets, action figures, etc. Animated shows like Marvel’s Guardians of the Galaxy preserve the spirit of the characters while being not quite as violent or mature as their live-action counterparts. This is nothing new, either. Older shows like Batman: The Animated Series and X-Men proved faithful to the source material without alienating younger audiences.

The current slate of Marvel and DC films falls in the PG-13 range. While Marvel is a bit more whimsical in their content and DC a bit darker (as per tradition), the films are generally accessible to a younger age, even if some of the heavier themes elude them. However, the onus is on both companies to introduce their characters in an appropriate manner for all ages, and they’ve done exactly that. There are so many avenues for children to enjoy these characters––learning to read books, LEGO sets, action figures, etc. Animated shows like Marvel’s Guardians of the Galaxy preserve the spirit of the characters while being not quite as violent or mature as their live-action counterparts. This is nothing new, either. Older shows like Batman: The Animated Series and X-Men proved faithful to the source material without alienating younger audiences.

My point is that superhero culture and fandom extend far beyond the films. There’s something superhero-oriented out there for everyone, and new fans are being made every day. Variety is a necessity for lasting success as a business and artform. Not every superhero comic or film is cut from the same stylistic mold, which brings me to––

The Scary, Dreaded R-Rating

With the recent success of Deadpool and rumor that Batman vs. Superman will have an R-rated home video cut, there’s been a lot of talk about ratings. All superhero films don’t need to push the envelope into R territory, but there are certain stories and characters that need the freedom of an R rating to be faithful adaptations of the source material. Deadpool is not a character for kids, never has been, and neutering him in an attempt to make more money would’ve been a terrible decision based only on business fears, not creative integrity. Plenty of comics are better suited for the R realm, such as Kick-Ass and Watchmen. Why can’t popular but more violent characters like Wolverine enjoy both mainstream PG-13 team films and grittier, R-rated solo affairs?

As I’ve mentioned in a previous piece, I think it’s dangerous to merely eliminate onscreen blood and reduce cursing simply to obtain a PG-13 rating when the core violent acts remain the same. Take the “Unleashed, Extended Edition” of The Wolverine––the extra blood from his lethal claws adds more dramatic weight and consequence to his actions, even if he’s still not quite the full-on berserker from the comics. What does it say if his claws are dicing through people with nary a drop of blood?

Yashida: “Monster. No pain? You have no…”

Wolverine: “Oh, yeah. Pain. Plenty of pain.”

Yashida: “How old are you?”

Wolverine: “It’s been a long time. Many wars. Understand? Too many fuckin’ wars.”

The Wolverine

When all’s said and done, the MPAA rating system itself is inane. A spatter of blood? R. More than one “fuck?” R. These arbitrary rules can restrain filmmakers and have studios worrying about their investment return instead of focusing on the best possible story. The very concept of the Suicide Squad––mass murderers forced into a team of misfits––seems like something that should have more edge than a PG-13 film can provide within those nonsensical boundaries. Avengers and Spider-Man have no business being rated R, but there has to be the possibility for other franchises to exist within a more adult world. Studios and filmmakers should strive to service the creative integrity of the story and characters––regardless of the rating.

A Healthy Escape

Part of the reason I love superhero films, and why they are so damn successful, is because the world is in a tough spot. For many filmgoers, movies are entertainment, a way to put aside their daily struggles. TV and the Internet bombard us with doom and gloom. Politics in our country are worse than ever, and people are beyond frustrated with the government’s squabbling. Critically acclaimed movies like Spotlight don’t make a billion dollars because, more often than not, people don’t want to pay to be dragged through the muck. There’s an immense appeal to larger than life figures cutting through the red tape garbage and making the world a better place. Defeating evil. Getting the job done. What’s wrong with being in that mindset for two hours? Nothing. Wanting to escape reality doesn’t mean that fans are turning a blind eye to the world’s suffering. There’s room in people’s minds to enjoy these stories and be socio-politically conscious.

“Comic books, and the movies they’ve spawned, no longer operate as the elementary morality tales that grew out of the Depression and Second World War that followed it.”

Sean P. Carlin

Sorry, Sean, I have to disagree once more. Back then, Captain America and other World War II-era comics were borderline propaganda because that was what the world needed. It’s uninformed to say that morality and social relevance are gone from comics and superhero films. For example, Captain America: The Winter Soldier has very poignant themes about the rise of a surveillance states and deterrence based on fear.

Nick Fury: “For once, we’re way ahead of the curve.”

Steve Rogers: “By holding a gun at everyone on Earth and calling it protection.”

Nick Fury: “You know, I read those SSR files. Greatest generation? You guys did some nasty stuff.”

Steve Rogers: “Yeah, we compromised. Sometimes in ways that made us not sleep so well. But we did it so the people could be free. That isn’t freedom, this is fear.”

Captain America: The Winter Soldier

Likewise, every single X-Men movie deals with segregation, intolerance, and prejudice. The best stories have continued to tackle important issues and commentate on modern events such as 9/11 and the rise of terrorism or gay marriage. Lack of diversity in superheroes has been a documented struggle, but strides are being made on that front as well.

Nightcrawler: “You know, outside the circus, most people were afraid of me. But I didn’t hate them. I pitied them. Do you know why? Because most people will never know anything beyond what they see with their own two eyes.”

X2: X-Men United

I believe the comic industry wants to be progressive, one based on inclusion not exclusion. It’s not perfect, but the stories are as relevant today as they’ve ever been.

I believe the comic industry wants to be progressive, one based on inclusion not exclusion. It’s not perfect, but the stories are as relevant today as they’ve ever been.

Superhero Heyday or Oversaturated Market?

What Sean finds most distressing is the apparent dominance of the superhero genre in filmmaking, one that shows no signs of slowing. Having spent a decade working in Hollywood as a screenwriter, I know how difficult it is to sell original material, especially stories that would prove costly to produce. I’m a fantasy writer with a specialty in epic world creation, so trust me, I’ve been there. Studios are very reticent to commit to anything without a pre-existing fanbase or established property. “Pre-awareness” is one of the many buzzwords for this trend. It’s a problem, but superhero films are only one factor. Sequels, adaptations, and reboots are just as prevalent––if not more––in Hollywood’s recent slate of movies. Hunger Games, Harry Potter, Divergent, Creed, Star Wars, James Bond, the upcoming Blade Runner and Predator sequels––their success comforts executives whose jobs depend on box office returns, and I don’t blame them. Any industry would be reticent of a $100 million risk.

What Sean finds most distressing is the apparent dominance of the superhero genre in filmmaking, one that shows no signs of slowing. Having spent a decade working in Hollywood as a screenwriter, I know how difficult it is to sell original material, especially stories that would prove costly to produce. I’m a fantasy writer with a specialty in epic world creation, so trust me, I’ve been there. Studios are very reticent to commit to anything without a pre-existing fanbase or established property. “Pre-awareness” is one of the many buzzwords for this trend. It’s a problem, but superhero films are only one factor. Sequels, adaptations, and reboots are just as prevalent––if not more––in Hollywood’s recent slate of movies. Hunger Games, Harry Potter, Divergent, Creed, Star Wars, James Bond, the upcoming Blade Runner and Predator sequels––their success comforts executives whose jobs depend on box office returns, and I don’t blame them. Any industry would be reticent of a $100 million risk.

Despite the fancy infographic in Sean’s essay, the superhero genre doesn’t have a monopoly on the movie industry. Well over 100 major studio films are released every year. There’s no shortage of stuffy dramas recognized every awards season, but we hear more about superhero films because studios pump more money into marketing their projects that generate the most profit. But this doesn’t change the fact that there are plenty of other movies out there, and it’s on the audience to make those popular. A lot of people talk a big game about wanting more independent films and fewer blockbusters, but how many of them actually pay to see those little movies in theaters?

Marvel and DC are putting so much effort into gathering immense talent. Directors, writers, A-list actors, and craftsmen behind-the-scenes…they are all at the top of their game and coming together with a passion for these stories. They aren’t averse to taking risks, either. Who would’ve thought that Guardians of the Galaxy would be a smash hit beloved by critics and audiences? Or Ant-Man? It’s hard to remember that Iron Man wasn’t always the megastar that he is now.

Dedication and quality breed success.

Ultron: “Worthy? How could you be worthy? You’re all killers. You want to protect the world, but you don’t want it to change. There’s only one path to peace…your extinction.”

Avengers: Age of Ultron

One Universe, Infinite Stories

The Marvel Cinematic Universe is an achievement for the ages, and like all success, others are attempting to replicate it. Sean labels the MCU an example of postnarrative storytelling where “nothing gets resolved, you see, when there’s always another subplot to cut away to.” It’s the responsibility of the writers to ensure that each individual tale has relevance and changes the characters instead of just setting up the next convergence of heroes, and I believe the MCU has been successful. Take Captain America’s arc since his first solo outing to the upcoming Civil War: he’s gone from a “yes, sir” patriot in WWII to a man displaced from time and wary of modern intelligence compartmentalization to a fallen icon branded a vigilante. Again, not every film finds the same level of dramatic success, but I firmly believe that each of these stories can stand on its own.

The Marvel Cinematic Universe is an achievement for the ages, and like all success, others are attempting to replicate it. Sean labels the MCU an example of postnarrative storytelling where “nothing gets resolved, you see, when there’s always another subplot to cut away to.” It’s the responsibility of the writers to ensure that each individual tale has relevance and changes the characters instead of just setting up the next convergence of heroes, and I believe the MCU has been successful. Take Captain America’s arc since his first solo outing to the upcoming Civil War: he’s gone from a “yes, sir” patriot in WWII to a man displaced from time and wary of modern intelligence compartmentalization to a fallen icon branded a vigilante. Again, not every film finds the same level of dramatic success, but I firmly believe that each of these stories can stand on its own.

Much has been written about superheroes as modern mythological figures. Think about this: what if the ancient Egyptians, Greeks or Romans had the technology and storytelling capabilities of today? They would be replicating (or inventing) the MCU gameplan. After all, what is a pantheon of gods but an early shared universe? All of the myths and parables of these mythologies exist together, each with its own message but still contributing to a larger understanding of both their world and ours. If they could’ve made movies, I guarantee characters like Achilles or Zeus would’ve been as heavily featured as Superman or Batman.

“The same origins, the same conflicts, the same tired hagiographies you’ve sat through a thousand times before.”

Sean P. Carlin

Repetition doesn’t have to mean stagnancy. How many times have Shakespeare’s stories been adapted? Discovering new depths and relevance for the superheroes (while remaining familiar) has proven key to their enduring legacy, and under all of Sean’s arguments is a love for Batman that I find a bit contradictory.

“Somehow, over three decades and counting, Batman had grown alongside me, becoming more mature and complex as I grew more mature and complex; he remained personally relevant throughout the different seasons of my life. And just when it seemed I’d finally outgrown him, he evolved further still—into his most fascinating permutation to date.”

Sean P. Carlin

Isn’t that quote a resounding endorsement of superhero films, a recognition that they evolve for every generation without necessarily retreading the same material? It’s why we keep coming back for more. Batman is the most popular example of this, having been played by no less than 6 actors.

These characters are cultural landmarks with a cyclical nature. Eventually, actors and directors change but the popularity remains. With each new permutation, the characters are reinvented and given fresh relevance. The MCU is still in its first iteration, but the torch will be passed as it has for decades. For Sean, Nolan’s Batman films marked an artistic apex for the character, but each time the Caped Crusader hits cinemas is a chance for a different fan to feel the same way. With Batman vs. Superman, a whole new audience may be discovering a love for these heroes.

The MCU is nothing if not ambitious. That ambition pushes everyone involved to elevate their talents while inspiring others like DC to follow suit. If the result is higher quality filmmaking that entertains millions, how can that be anything but positive?

Fandom Never Dies

There’s no simple answer for why superhero films are so popular. Many factors influence audiences, from the increased role of technology in our lives to the constant transparency of social media. Perhaps it’s just that going to these films makes people happy.

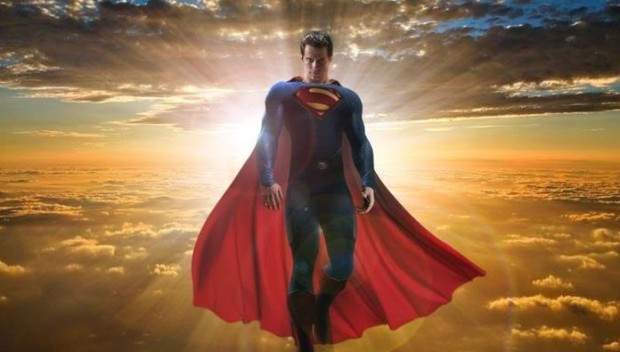

Jor-El: “You will give the people of Earth and ideal to strive towards. They will race behind you, they will stumble, they will fall. But in time, they will join you in the sun, Kal. In time, you will help them accomplish wonders.”

Man of Steel

The joy brought from a movie can’t be quantified in rotten tomatoes percentages or box office revenue, and I’ll never apologize for being a cinematic optimist. Too many fans (not Sean) nitpick flaws and take to the Internet to eviscerate franchises they claim to love. Remember that for every movie you didn’t like, there are other fans out there that had a blast.

My passion for superhero films isn’t going to change any time soon. I enjoy the experience on multiple levels and believe that these stories will continue to have a significant position in our culture for years to come.

Jeff,

Thanks so much for engaging me in a lively debate on this complex subject!

Rather than offer a point-by-point counterresponse — anyone interested in my views on these matters can read “The Great Escape” — let me instead offer this: When I began to ask why Gen X in particular loves superheroes so much — and, more to the point, what that says about us as both a generation and a collective culture (good, bad, or indifferent) — I came to the understanding that superheroes are a reminder of the linear, analog world we lost as a consequence of the Digital Revolution. We are the last generation that will have known the “analog world,” as it were, and make no mistake: We are emotionally traumatized by that (in ways we have not yet begun to understand or process).

Media theorist Douglas Rushkoff, upon whose work much of my own writings are based, posits that the popularity of zombie fiction right now reflects a longing for a simpler existence — one free from the omniscient telecommunications hum of text messages and Twitter and Facebook — and that when we can no longer envision that for ourselves, the imagination tends to indulge apocalyptic narratives: In the zombie apocalypse, after all, you may have to worry about a monster jumping out at you from behind every closed door… but at least, suggests Rushkoff, you’ll never have to answer another e-mail. In that context, The Walking Dead isn’t a nightmare scenario — it’s a wish-fulfillment fantasy.

As is, I would argue, the superhero story in its current incarnation. As I’ve written about previously, superheroes express our yearning to exercise control in a world where we feel powerless against the digital onslaught — that is the emotional need they fulfill in us at this moment in our history. But, here’s the lesson that teaches us: that once we learn to control all these pervasive, inescapable digital technologies the Information Age has wrought instead of what we’ve done so far — let them control us by misapplying them based on obsolete Industrial Age notions of how to use our time and resources to further capitalistic growth — and embrace the true, heretofore untapped potentials of a digital, postnarrative era, “where the object is no longer to win, but to keep the game going,” only then will we have a sustainable, non-zero-sum model of society in which we no longer need zombies or superheroes anymore to deal with our anxieties about the world that was versus the world that is; at that point, we’ll simply be focused on the would that can be.

So, for me, “The Great Escape” was ultimately an investigation into what our cultural fixation with superheroes — something you yourself don’t deny — is trying to tell us about ourselves, and extracting a larger takeaway from that. And what it tells me is this: that we don’t need fictional superheroics to feel vicariously empowered to effect actual change in the world around us — our own mere humanity is superheroic enough, provided we confront our apprehensions and empower ourselves through the technologies we’ve devised (and thus far surrendered control to). That’s the kind of meaningful lesson superhero stories can offer us if we’re willing to look in the mirror and ask ourselves why, as a culture, we’ve venerated the children’s characters of a previous century. I suggest we all take a closer look at our favorite wish-fulfillment fantasies, examine what wishes they fulfill, and then see if we can’t do that on our own without them. That would be a superheroic evolution indeed.

Sean

Sean,

Thanks for the comment! Let me ask you this: what do superheroes represent for Millenials? Clearly, superheroes are just as popular with that generation, if not more so, than Gen X. But unlike us, Millenials have never known adulthood without pervasive social media and technology. They don’t feel powerless by the digital onslaught, they embrace it. I wonder what they are taking away from the superhero genre. If it’s radically different than Gen Xers, that again speaks to the broad and ever-evolving appeal of the genre.

You’re very right in that we don’t NEED superheroes to face and deal with the world; right now they just happen to be the medium of choice. Throughout history, people have used various entertainment to process the world — poetry, theater, music — really anything creative can fit the bill. Fiction helps us digest reality. Sometimes people can only see truths when its presented through a story. Isn’t that why stories remain one of the most potent and diverse ways of communication?

Jeff

One of the great failings of Generation X, certainly insofar as our responsibilities as the custodians of pop culture go, is that we haven’t attempted to “pay forward” all the wonderful, original fantasy cinema the Boomers (Spielberg, Lucas, et al.) bestowed to us in the seventies and eighties (Star Wars, Indiana Jones, Ghostbusters, Gremlins, Back to the Future, etc.). No one, in my view, is more emblematic of this creative deficiency than J.J. Abrams (age 49): Who is he as a filmmaker? Well, he produces Mission: Impossible… but that’s an extension of Bruce Geller’s vision, not his own. He made the last two Star Treks, but, again, those are the product of Gene Roddenberry’s imagination. And now he’s being celebrated for Star Wars, the brainchild of George Lucas. So, again I ask: What does an actual J.J. Abrams movie look like? Well, we don’t really know. He cites Spielberg as a professional role model, but Spielberg (like his contemporaries Lucas and Carpenter and Zemeckis) made a name for himself by forging new cinematic territories: He gave us these incredible cultural treasures we all share, like Jaws and Indy and E.T. and Poltergeist and The Goonies. What has Abrams paid forward to the Millennials, exactly, except warmed-over second helpings?

And he’s not alone. As soon as a Gen X director establishes a name for himself with a successful original genre movie, he’s then seduced by the studios into helming yet more entries in the franchises of the previous century (of which superhero movies are admittedly only one facet). Cases in point: Rian Johnson (age 42) made Looper, now he’s directing Episode VIII; Gareth Edwards (age 41) made Monsters, now he’s got Godzilla and Rogue One: A Star Wars Story on his résumé; Colin Trevorrow (age 39) made Safety Not Guaranteed before moving on to Jurassic World and Episode IX; Josh Trank (age 32 — not quite Gen X, I’ll concede) made Chronicle, then tanked his promising career with Fantastic Four (and lost his shot at a Star Wars film for it); Neill Blomkamp (age 36) directed sci-fi originals District 9, Elysium, and Chappie, and shortly after renouncing “the whole corporate-sausage-factory notion of summer blockbusters,” signed on to do a fifth Alien movie (which has since, mercifully, been shelved).

Our generation was gifted with the most imaginative cinematic fantasies, but thus far all we’ve managed to do in return is recycle content rather than create it. And that, to me, is what the superhero onslaught is illustrative of: a certain (and troubling) creative bankruptcy, a lack of vision. Directors like Abrams and Trevorrow will likely have long, lucrative careers directing other people’s movies, but what are they contributing to the cultural tapestry, exactly? Will those guys ever be idolized like Spielberg and Lucas and Zemeckis? Even Lucas, for as much as fanboys hate him now, inspires passion, because his films meant so much to a generation — they both reflected and defined their times. Being a storyteller is a privilege, but it also comes with a responsibility to the culture, and I think the Gen X filmmakers of today have, by and large, failed to use their talent and muscle to champion new visions — some (many) of which may very well not creatively cohere, yes — in favor of serving up the same old fantasies of their own youth over and over and over again.

So, as for what the Millennials take from superhero cinema, I can’t say, but I do know this: They haven’t been given any new iconic cinematic heroes that might inspire and expand their imaginations the way we were. Instead, they’ve been force-fed our heroes, by a generation that’s drowning itself culturally in its own nostalgic yearning rather than taking inspiration from the stories of its youth and recasting them in its own image, as Star Wars was an evolutionary leap from Flash Gordon, Ghostbusters from the Bob Hope ghost comedies of the forties, Batman from Zorro. Christ, don’t we want to be remembered for having created something rather than having merely remodeled it?

Now, all that said, you’re certainly right: Repetition doesn’t have to mean stagnancy, as Shakespeare (among others) have proven; I myself have written extensively about how folkloric characters — specifically, comic-book heroes — are versatile enough to accommodate perennial reinvention. But, I do believe that Gen X — talkin’ ’bout my generation — ought to ask itself some tough questions about the kind of stories we’re creating, and whether they’ll inspire the next generation like the tales we’re endlessly retelling inspired us. And we certainly ought to give long, hard consideration to Alan Moore’s admonition: “I would also observe that it is, potentially, culturally catastrophic to have the ephemera of a previous century squatting possessively on the cultural stage and refusing to allow this surely unprecedented era to develop a culture of its own, relevant and sufficient to its times.”

So, mine isn’t a call to stop telling superhero stories so much as it is a plea to ask ourselves, as the custodians of pop culture (and probably not for much longer, at that), if we’re exceeding or even meeting the bar set by the last generation. And that’s a question each of us, as storytellers, can only answer for ourselves.

Damn. After your debate Sean i dont feel qualified to have an opinion!

But i enjoyed the read. It was severly informational. Learned so much.

Thanks Jeff.

That’s my secret, Kevin: I bludgeon you into submission!

And here’s a brief piece on the same subject by Scott Mendelson worth checking out.

I’ll say nothing of the points of this debate here. However, what I will say is that I’m all about the way you both have engaged in friendly, respectful and informative discourse coming from differing standpoints. I’ve never understood why agreement is a necessary component of true camaraderie and association for so many people. I literally have friends of mine on the furthest edges of political ideology, friends who really liked and respected and enjoyed one another through mutual association with me … until each found the other was of a different political mind. Silly.

Thanks for bolstering the idea that we really can agree to disagree, and not get our panties in a wad over it.

Erik,

Exactly! It’s all love, man. People will always disagree, but somewhere along the line a lot of us forgot how to present our arguments in a respectful manner. The anonymity of the Internet seems to give people license to let out their inner brat. Sean and I obviously have different views on the superhero genre, but we both understand and respect each other’s opinions. Right or wrong doesn’t factor into it. I only want to support fellow writers, not bash them to promote my own ideas. Thanks for the comment!

I had hoped when I wrote “The Great Escape” that it would provoke debate, and get everyone to think a little deeper about a form of storytelling that has become popular at best and pervasive at worst (depending on one’s perspective) — what it means to us individually and culturally. And I’m delighted that Jeff took such a (passionate) position that created so much room for discourse, and that Erik participated in that discussion! Just because Batman & Superman and Iron Man & Captain America can’t work out their differences like gentleman doesn’t mean we can’t!