Week 5 – The Scholar

Welcome back, dear readers. I apologize for not having this post ready on Monday, but who doesn’t like a fun Friday blog to cap off the week? For this entry, I’m doing something a little different and hope you’ll find it informative. I took a brief hiatus from skating to let my wrist heal while enjoying some much needed family time. I didn’t want to skip my weekly post, however, and happened upon a rather serendipitous discovery. While randomly combing through my old college essays, I unearthed a skateboarding gem. A diamond in the rough, if you will.

I was a very focused student during my schooling. I powered through numerous AP courses in high school and took summer courses in college to graduate from Boston College in three years. Summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa, all that good stuff achieved via consistent hard work. A 2002 summer “Youth in America” sociology course was the perfect chance to dive into the critical academics of skateboarding. After all, it was the only group or culture I’d ever been part of. By referencing the knowledge of scholars and professional skaters, I crafted a paper on the ebbs and flows of skateboarding, intricacies of the subculture, gender biases, and how skaters experience urban environments. Quite a mouthful, I know, but I was a wide-eyed student eager to dissect the cultural importance of my pastime.

I’m posting my complete original essay here, grammar mistakes and all. Certain sentences read a bit stiff and cringe-worthy at times, but I think there’s still a lot of good insight. You have to cut me some slack, I was only twenty and neck-deep in academia 24/7. I don’t prefer to do analytical writing or nonfiction anymore—even putting out my blogs can be like pulling teeth—yet how could I not share my vintage work in the digital age?

The essay also serves as a time capsule of sorts because so much has changed concerning skateboarding. From the culture’s modernization and increased presence of women in skating, to the near-universal acceptance of it as a legitimate sport, skateboarding is a far cry from where it was eighteen years ago.

Skateboarding: A Critical Analysis

Skateboarding has been criticized and falsely labeled as a “deviant” activity since its birth decades ago. However, the modern commercialization of it has exposed skateboarding for what it really is: a subculture and art form. This paper is an intricate look into the subculture of skateboarding including its history, and the sociological themes present within it.

Like any subculture, skateboarding has had a rich history. It has gone through four major “waves” to establish itself as a legitimate subculture in American society. The first “skateboard” was invented in the early 1900s. Kids would attach roller skate wheels to a two by four and a milk crate. However the first commercial skateboard was invented after World War II. 1959 saw the dawn of the commercial skateboard industry that brought exciting new technology, such as clay wheels. As the 60’s approached, skateboarding gained a respectable size following within the surf crowd. By 1964 kids had labeled their activity “sidewalk surfing”[i]. In 1963 Larry Stevenson’s company, Makaha, designed the first professional skateboards. A team was formed to promote the product, an idea that foreshadowed the future of the skateboard industry. However in 1965 skateboarding had its first major crash. The crash was due to “inferior product, too much inventory, and a public upset by reckless riding”[ii]. Clay wheels did not grip the road well and people were having horrid falls. Thus skateboarding recessed for a time.

While skateboarding didn’t disappear entirely after the crash, it was definitely in a state of hibernation. However in 1973 Frank Nasworthy invented a product that resurrected skateboarding: urethane wheels. After this skateboarding was once again in full swing. Truck manufacturers (“trucks” being the piece of metal attached to the skateboard that holds on the wheels) began to spring up. The first outdoors skate park was opened in 1976 in Florida and people began to skate emptied pools. However the biggest mark of the second wave of skateboarding was the invention of the “ollie” by Alan Gelfand. The “ollie” (pressing down on the back of the board with one’s back foot and jumping up while sliding one’s front foot to gain air) would become the staple trick in skateboarding. Yet skateboarding was doomed again as insurance problems rose up. Park began to close and by the end of 1980 skateboarding was once again almost non-existent[iii]. However a breed of hardcore skaters kept it alive with skate sessions on their backyard ramps.

In 1981 Thrasher magazine was developed for the hardcore skateboarders. In 1983 Transworld Skateboardingmagazine was launched and manufacturers were beginning to see the sport on the rise. Vert ramp skating became immensely popular. Tony Hawk (who would later become a skateboard icon) appeared on the scene with his incredible talent. Towards the end of the decade skateboarding shifted to “street skating”, a “new school” style that focused more on the ollie based maneuvers. However, by 1991 a “worldwide recession” hit and the skateboard industry was fatally affected[iv]. Manufacturers faced massive financial losses causing the industry to lose faith in the sport and skating to decline.

Skateboarding would not stay down for long. TV and the Internet provided more awareness to the sport. Also people from the 70’s who had skated were having kids and wanted to pass on their former passion. Thus by the mid 1990’s skateboarding had reemerged in it’s fourth wave. In 1995 the sport began to get commercialized with the invention of the X-Games. Focus is still placed on street style and manufacturers are popping up all over the place. The skateboard industry had become a gigantic money making machine. Parks began to reemerge[v]. Finally skateboarding had entered a secure phase, and had developed a dominant subculture in youth across American society.

Recently there has been a lot of sociological study concerning the subculture of skateboarding. Dr. Becky Beal is perhaps the field’s leading expert. She has explored skateboarding as a form of social resistance, the authenticity and values involved in the sport, and how it acts as a form of alternative masculinity.

Dr. Beal notes that “popular culture is a site in which both hegemonic and counter hegemonic interests are expressed and lived simultaneously”[vi]. Skateboarding is no exception. Hegemony is the “process by which ideologies become materialized through the everyday experiences of people: how ideologies are internalized, struggled over, negotiated, opposed, and lived out”[vii]. When people actively consent to hegemonic forms, they are not only acknowledging ideas, but arranging their actions around those ideas as well. Resistances to hegemonic forms, such as subordinate subcultures like skateboarding, are important because they are a form of social change. Rather than being a stagnant group, the subculture of skateboarding is a dynamic one that is continually being shaped by both hegemonic and counter hegemonic interests[viii].

In mainstream North American sport capitalist ideologies and corporate bureaucracies are dominant. With this comes a “standardization of cultural forms” that has a tendency to “naturalize dominant values” and produce a “loss of choice and a loss of awareness of choices”[ix]. In skateboarding there is a prominent, blatant resistance to this type of corporate relation. However since skateboarding displays both hegemonic and counter hegemonic behavior, not all people dislike the corporate aspect of it. Those who embrace corporate clothing and paraphernalia are labeled “rats” by those who reject the professionalization of the sport[x]. The styles of expression vary greatly among skateboarders and are particularly associated with the type of music one listens to. Yet even though skateboarders recognize their internal differences, the majority also embraces their own subculture status[xi]

The subculture also resisted corporate bureaucracy by creating norms and relations that stressed devalued competition and participant control [xii]. A skateboard competition is an example of social resistance because it is so drastically different from any other sports competition. It breaks the common rules of competition. It is more about watching, fraternizing, and meeting new people. The skateboarders de-emphasize the actual competition[xiii]. Skateboarders compete more against themselves than others. Everyone tends to give each other an amazing amount of physical and emotional support. The majority of skateboarders do not use their skills to belittle others. As a general rule one does not skate against someone, but with them, even in competition[xiv]. Due to these vastly different ideologies, the skateboard competition is a passive example of social resistance to the corporate professionalization of the subculture.

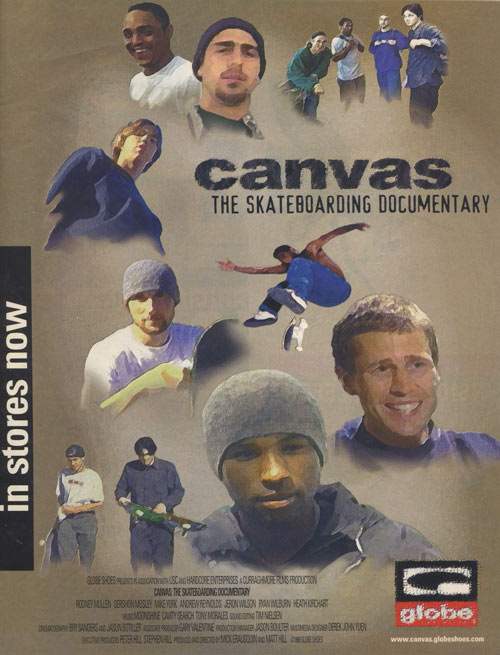

Along with devaluing competition, participant control and individualism are core values of the skateboard subculture. Many people are drawn to skateboarding because there are no positions, no championships, no end goals, and nothing “to win”. It is controlled personally; you are your own expert. It is an extremely self-defining activity because “the participants determine the boundaries and criteria for their spot which allows them to create an activity that fits their needs”. Also, a competitive attitude was a negative attribute. Mainly skaters desired each other to make an effort to learn how to skate[xv]. There are no strict rules to guide your progression either. This gives the participant a certain feeling of empowerment and control. Professional skateboarder Ryan Wilburn discussed this fact in the documentary Canvas: “skateboarding is like the craziest drug in the world, you know, it shows me love and it shows me hate, but no matter what my skateboard will always be there”[xvi]. The dedication to creativity and self-expression of skateboarding are valued as means of non-conformity. Skateboarding is an outlet for individual expression. Every individual is encouraged to create his or her own personalized form of skateboarding[xvii]. This tends to draw criticism because people are intimidated by the spontaneity of the sport due to its demand for unstructured, expressive interaction. Professional skater Mike York believes people criticize the sport because “we’re doing something we love to do, and I think people that don’t do that, hate that, they hate it so much”[xviii]. People who quit skating early on are possibly looking for a “predetermined, rebellious meaning” instead of and outlet for their creative energies[xix].

Skateboarding is a subculture; someone who wishes to be a part of it has to gain authenticity. Embracing the central values of participant control and devaluing competition appear to be the key to gaining the status of a “legitimate” skateboarder in the subculture. These values directly challenge the norms and ideologies of structured, professionalized sports. As noted previously, those who ignore these values and conform to the corporate aspects of skateboarding tend to be labeled as “rats”[xx]. Basically to be an authentic skateboarder one must embrace the central aspect of the individual expression of self. When skateboarders truly skate for themselves, the sport transforms into what it really is: art.

Critics who refer to skateboarding as a deviant act enrage skateboarders, especially professionals. Mike York wonders, “How can you say that we’re idiots? We’re using our minds on a whole other level. They don’t see the art form in it”. The art is in the individuality of the sport. “No one’s art will look like yours. Everyone can draw a house but the house will look different right? Anyone can do a 360 kickflip, but it will look different[xxi]. The general feeling among skateboarders is that they are creating art. Anything that has so much effort and energy used to create something is art. Everyone’s style is unique and does not rely on a judge to be legitimate. It is a shame that people continue to criticize skateboarding rather than taking a step back to really see its beauty and genius.

The skateboard industry itself often reflects the values and ideals of the subculture. Since success in the industry requires a complete grasp of the culture, skateboarders themselves are most likely to be successful. Because of this fact the industry is centered on the idea of “sponsorship” (the exchange of goods for services). As a skateboarder becomes increasing talented, he or she may be “picked up” by a company. They will then get free skateboards etc. in exchange for representing that company’s goods. Sponsored professionals use boards that have graphics on the bottom that are personalized and tend to reflect themselves[xxii]. Professional skateboarder Rodney Mullen commented on being a professional in Canvas, “There’s this amazing feeling of being a part of something where you’re not just doing what other people do, yet you’re a part of it and needed”[xxiii]. In this quote Rodney summarized the basic dichotomy of skateboarding: the desire to be an individual and yet be accepted in the subculture at the same time.

In the industry, self-expression and individualism are important as well. Advertising companies try to be extremely inclusive, thus fueling the skateboarders desire for the insider mentality. Ads may be so obscure that only a skateboarder could understand them. These types of ads serve another function as well. Not only will insiders be drawn, but “outsiders” will strive to become insiders as well[xxiv]. Along with the insider mentality, magazines such as Thrasher and Transworld try to appeal to skateboarding’s dedicated lifestyle, long-term commitment to the sport, and the history. Thus the industry is basically a massive reflection of the subculture’s values and norms.

The subculture of skateboarding is also an example of how masculinity is not “naturally” predetermined or universal, but rather it is “a creation of the participants which varies according to the social context”[xxv]. Skateboardings emphasis on participant control, self-expression, and open participation is vastly different from the “hegemonic values” of conformity and elite competition. Skateboarding is a form of “alternative masculinity” because the skaters differentiated themselves from the norm, or “jock” image. The flexibility of skateboarding is the prime component of this alternative. Skateboarders feel they are more flexible to explore and express themselves individually, rather than doing exactly what everyone else is. The lack of formal structure and judging is invaluable in skateboarding. There is no such thing as a “perfect” trick or technique. In skateboarding, “you never lose”[xxvi]. All of these aspects of skateboarding make it a legitimate form of alternative masculinity.

However there are contradictions in skateboarding’s alternative subculture. While it steers away from the structure of formal sport, it still subconsciously retains some of the ideology of male superiority. While skateboarding is extremely informal and allows people to make their own rules, it also allows what Dr. Beal calls “gender stratification”[xxvii]. Sex-segregation in skateboarding is usually not a conscious aspect of the male skateboarders. The dominant male ideology of “natural” differences between males and females plays a large role in sex-segregation. Many males feel that skateboarding does not fit their preconceived image of what a “female” should be. The risks of bodily harm such as bruises and cuts does not seem to mix with their ideas of the “feminine” woman. Thus many female skaters get patronized because the males do not believe they can handle the pain involved with the sport. Some people even have the false belief that females do not “naturally” have the skills to be a skateboarder. Perhaps the most prominent deterrent of female skateboarders is the idea that it does not fit the female “social role”[xxviii]. As ignorant as it may be, many male skateboarders believe that girls do not skateboard because it is something they would not be interested in.

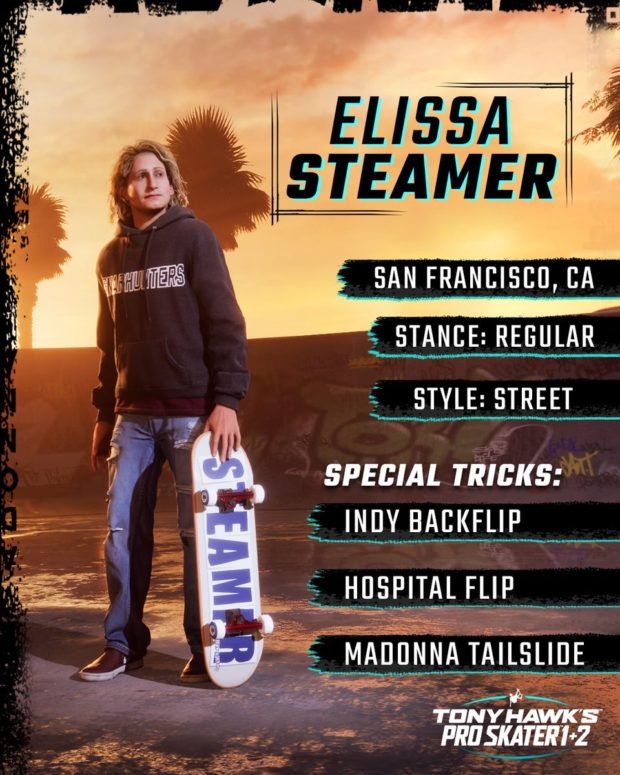

All of these gender-based factors have caused many females to avoid skateboarding as an activity. However, those who do choose to skateboard have a harder time gaining authenticity. Many females will dress like a skateboarder, or hang around skateboarders to gain popularity, but do not actually embrace the sport. These types of girls are called “Betties” by male skateboarders. A female who wishes to be accepted has to defeat this initial prejudice and establish herself as a legitimate member of the subculture. It is unfortunate that girls have to try harder to achieve the same respect as males. Yet once they are able to overcome the barriers they can be accepted[xxix]. Professional skateboarder Elissa Steamer has gained the respect of the entire industry with her skill. She is an icon for girls who respect the sport and wish to progress in it with equality.

Possibly one of the most interesting aspects of the subculture of skateboarding is how a skateboarder interacts with urban space. Iain Borden refers to urban space as “a continual reproduction, involving not just material objects and practices, not just codified texts and representations, but also imaginations and experiences of space”[xxx]. Skateboarding is a unique kind of urban space production because it utilizes objects and spaces yet does not produce any objective “thing”. Skateboarding is able to both represent and speak of the city without using theory or texts[xxxi].

Skateboarding is ironic because it brings together “a concern to live out an idealized present, trying to live outside of society while being simultaneously within its very heart”[xxxii]. To “produce” themselves this way skateboarders must perform their activity in the city. They speak their meanings and critique the city through their “urban actions”. The central critique of skateboarding ends up being “a rejection of the values and of the spatio-temporal modes of living in the contemporary capitalist city”[xxxiii]. Skateboarders see the city as a set of objects. To see the city as objects is to fail to see its character, however this is how a skateboarder views the objective nature of the city. A skateboarder treats all the surfaces of the city, from handrails to benches, as the physical ground on which he or she “operates”. By focusing only on certain elements such as walls or banks, the skateboarder treats urban space as a “set of floating, detached, physical elements isolated from each other” rather than a totality[xxxiv]. It is in this way that certain areas or buildings get known for one particular aspect rather than as a whole, such as the “Brooklyn Banks”. What ties these random elements together is an entirely unique and separate logic developed by the skateboarder’s movement from one urban element to another. These “strategies of embracing architecture” offer a unique perspective where the skateboarder’s “space-time become a flow of encounters and engagements between board, body, and terrain” rather than a discontinuous series of walls and surfaces[xxxv]. Thus skateboarding is more of an aesthetic than an ethical practice. A skateboarder uses the elements of the city to create an alternative reality. Skateboarding is then a way of speaking to the city, and a different way of communicating meaning. Through the continual performance of the skateboarder, meaning for the urban space is established[xxxvi].

Skateboarding is one of the most unique subcultures of the youth in America. Its long, wave-like history reflects the dedication and persistence of those who participate in the sport. As a subculture is a set of values based around individuality that determine authenticity. However, females are still struggling against some subconscious masculine tendencies of the male skateboard community. Skateboarding is also fresh and insightful in the way that it represents the urban city. It is sad that there are still ignorant people who still believe skateboarding is a deviant act. It has evolved into a subculture, a lifestyle where youth can be artistically expressive and creative. Professional skateboarder Ryan Wilburn summed up the entire skateboarding mindset in one quote, “I learn more everyday on my skateboard, like real life stuff. In the end it’s an opportunity. You can step on a skateboard and there’s so many different paths you can take”[xxxvii].

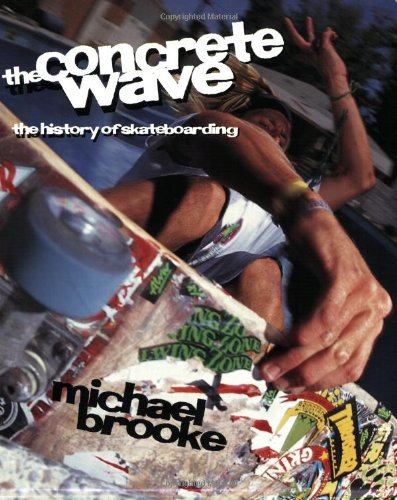

[i] Brooke, Michael. The Concrete Wave: the history of skateboarding (Los Angeles: Warwick Publishing, 1999), 16.

[vi] Beal, Becky. “Disqualifying the Official: An Exploration of Social Resistance in the Subculture of Skateboarding”, Sociology of Sport Journal 12 (1995): 264.

[vii] Beal. “Disqualifying the Official: An Exploration of Social Resistance in the Subculture of Skateboarding”, 254.

[ix] Donnelly, P. “Sport as a site for popular resistance”. In R. Gruneau (Ed.), Popular cultures and political practices(pp 69-82). Toronto, ON: Garamond Press (1988).

[x] Beal. “Disqualifying the Official: An Exploration of Social Resistance in the Subculture of Skateboarding”, 256.

[xi] Beal. “Disqualifying the Official: An Exploration of Social Resistance in the Subculture of Skateboarding”, 257.

[xii] Beal. “Disqualifying the Official: An Exploration of Social Resistance in the Subculture of Skateboarding”, 256.

[xiii] Beal. “Disqualifying the Official: An Exploration of Social Resistance in the Subculture of Skateboarding”, 260.

[xiv] Beal. “Disqualifying the Official: An Exploration of Social Resistance in the Subculture of Skateboarding”, 261.

[xv] Beal, Becky. (1999) “Skateboarding: An alternative to mainstream sport”. In Inside sports: Social research on involvement in sport and physical activity. Jay Coakley & Peter Donnelly (Eds.) Routledge, 2.

[xvi] Globe Shoes “Canvas: the skateboarding documentary”. A Curraghmore production. 40 min. Ryan Wilburn interview. Globe shoes, 1998. Videocassette.

[xvii] Beal, B. & Weidman, L. “Authenticity in the skateboarding world”. In S.

Sydnor & R. Rinehart (Eds). To the extreme: Alternative sports inside and out.

SUNY Press, 2.

[xviii] Globe Shoes “Canvas: the skateboarding documentary”. A Curraghmore production. 40 min. Mike York interview. Globe shoes, 1998. Videocassette.

[xix] Beal, B. & Weidman, L. “Authenticity in the skateboarding world”, 4.

[xx] Beal, B. & Weidman, L. “Authenticity in the skateboarding world”, 5.

[xxi] Globe Shoes “Canvas: the skateboarding documentary”. A Curraghmore production. 40 min. Mike York interview. Globe shoes, 1998. Videocassette.

[xxii] Beal, B. & Weidman, L. (In press) “Authenticity in the skateboarding world”, 7.

[xxiii] [xxiii] Globe Shoes “Canvas: the skateboarding documentary”. A Curraghmore production. 40 min. Rodney Mullen interview. Globe shoes, 1998. Videocassette.

[xxiv] Beal, B. & Weidman, L. “Authenticity in the skateboarding world”, 8.

[xxv] Beal, B. (1996) Alternative Masculinity and Its Effects on Gender Relations in the Subculture of Skateboarding. Journal of Sport Behavior 19, 212.

[xxvi] Beal, “Alternative Masculinity and Its Effects on Gender Relations in the Subculture of Skateboarding”, 213.

[xxvii] Beal, “Alternative Masculinity and Its Effects on Gender Relations in the Subculture of Skateboarding”, 214.

[xxviii] Beal, “Alternative Masculinity and Its Effects on Gender Relations in the Subculture of Skateboarding”, 215.

[xxix] Beal, “Alternative Masculinity and Its Effects on Gender Relations in the Subculture of Skateboarding”, 216.

[xxx] Borden, Iain. “A Performative Critique of the American City: the Urban Practice of Skateboarding”. The Journal of Psychogeography. http://www.psychogeography.co.uk/borden_on_skateboarding.htm, 1.

[xxxii] Hutchison, Ray (Editor). “Constructions of Urban Space” Stamford: Jai Press, 2000. 144.

[xxxvii] Globe Shoes “Canvas: the skateboarding documentary”. A Curraghmore production. 40 min. Mike York interview. Globe shoes, 1998. Videocassette.

Loved it