My upcoming novel, Fall From Grace, is an epic with moments of explicit violence bred from the horrors of warfare. The grisly, vicious imagery will disturb, upset, and even offend some readers. Good. The reality of violence should be abhorrent and stay with you long after the story is done. Unfortunately, entertainment has become so driven by money that content is watered down at the detriment of the material’s intention. Hypercritical rating systems have caused violence to be sanitized by inane rules on what can be shown or even heard. This doesn’t address the issue of violence; it only implies a lack of any actual consequences. What’s more damaging: understanding the grim weight of a story’s violent content or being “protected” by a sterilized version of the exact same scenarios?

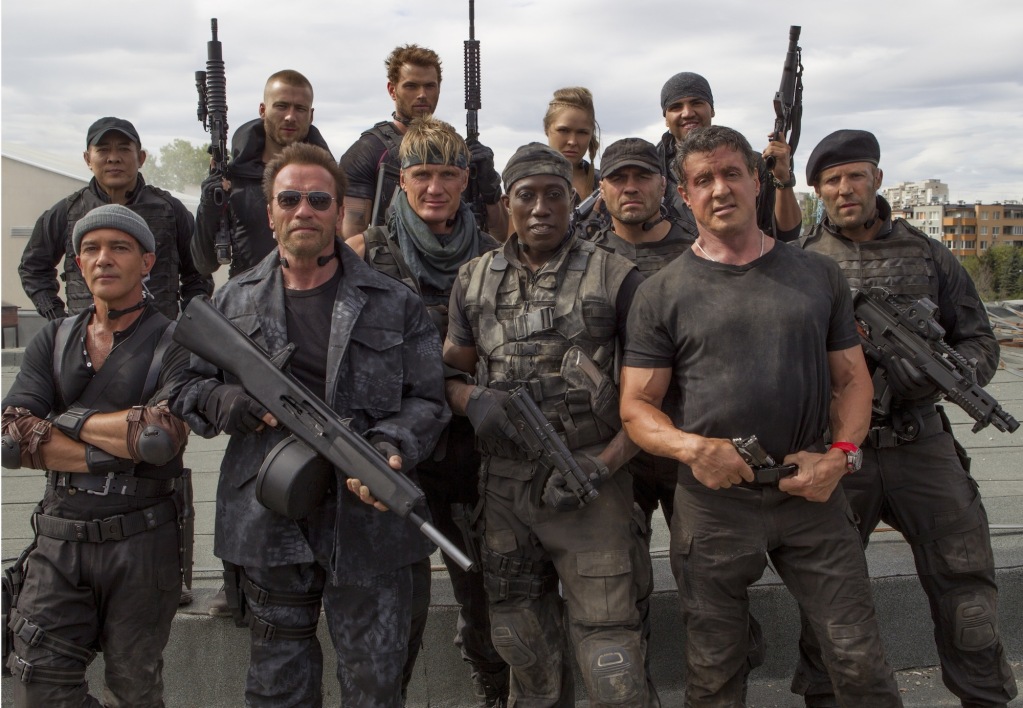

Movies are the worst offender because of the cursed PG-13 rating (and don’t even get me started on the oddball TV-14 / TV-MA system of television). Some of the most violent movies with the highest death counts are PG-13 because of little or no on-screen blood. One of the biggest recent examples is The Expendables 3, a film I enjoyed but that was castrated by almost 100 cuts to achieve a PG-13. Stabbing someone once is fine, but three times? Nope. Gunning men down is A-OK as long as they don’t bleed.

Movies are the worst offender because of the cursed PG-13 rating (and don’t even get me started on the oddball TV-14 / TV-MA system of television). Some of the most violent movies with the highest death counts are PG-13 because of little or no on-screen blood. One of the biggest recent examples is The Expendables 3, a film I enjoyed but that was castrated by almost 100 cuts to achieve a PG-13. Stabbing someone once is fine, but three times? Nope. Gunning men down is A-OK as long as they don’t bleed.

People still die in the movie. By the dozens. Mounds of corpses in every action scene.

Nothing about the film’s violence has changed by making it PG-13 other than scrubbing any imagery that would hit you in the gut and make you take pause. Bullet wounds aren’t bloodless affairs. They tear flesh and destroy internal organs. Even a fistfight can break orbital bones, cause brain damage, or worse. In the ‘80s, these types of action films were always rated R with at least some semblance of wound realism in a genre known for high body counts. Cutting out the blood is not only irresponsible, it actually makes the action more gratuitous by turning the dead into lifeless, inorganic dolls.

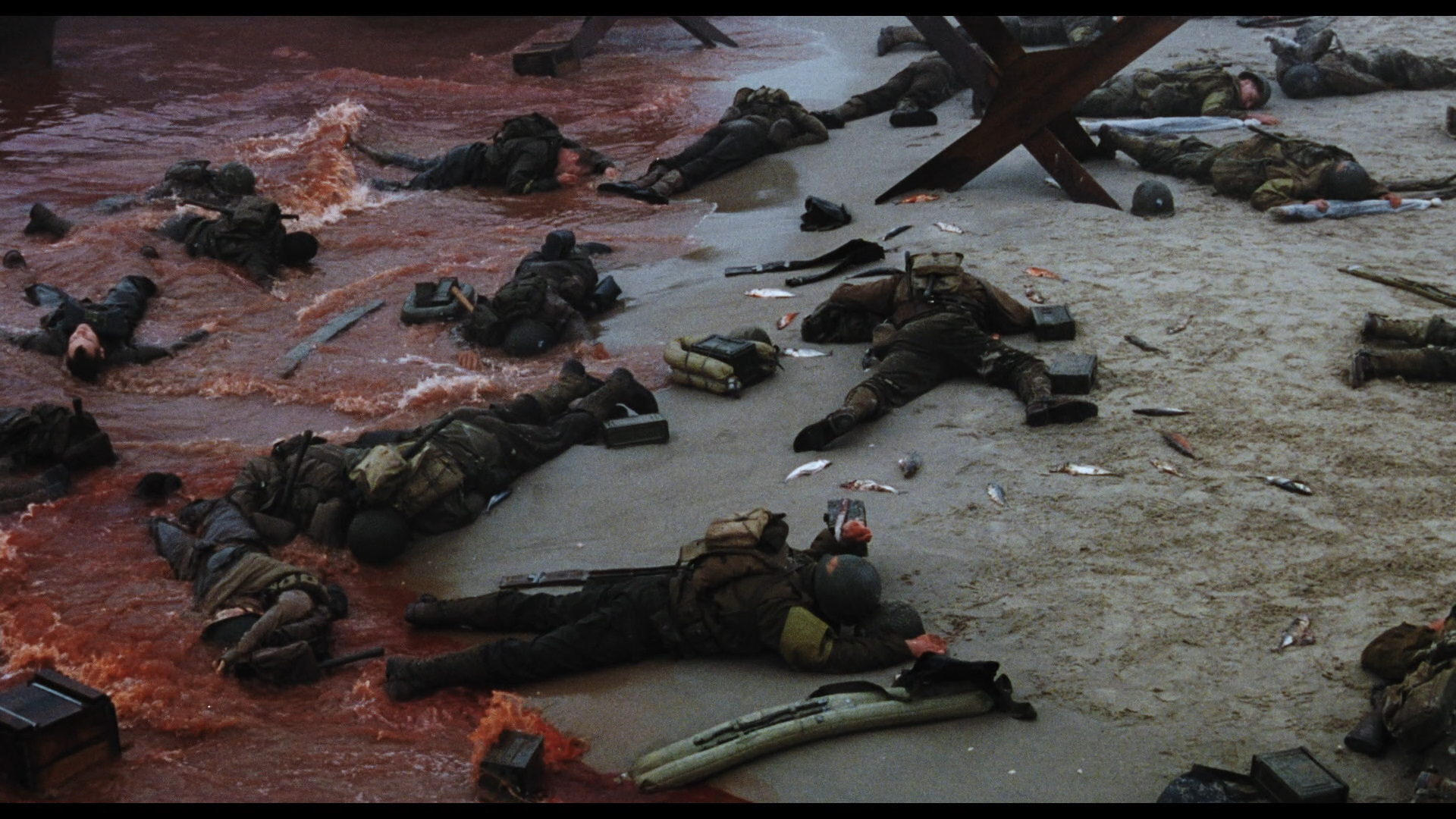

Anemic war films offend me the most. Denying the lethality of war belittles the memory of those who died (if it’s a true story) or hurts the narrative by diminishing its fictional characters’ sacrifices. Can you imagine if the opening sequence in Saving Private Ryan had been censored? Or if American Sniper cut away from the damage of Chris Kyle’s rifle shots? Gore doesn’t have to be 100% true to life––in the American Sniper script, a bullet is described as blowing the vertebrae out of an insurgent, a detail wisely discarded––but it’s beyond insulting to insinuate that war is something other than a massive loss of life.

Anemic war films offend me the most. Denying the lethality of war belittles the memory of those who died (if it’s a true story) or hurts the narrative by diminishing its fictional characters’ sacrifices. Can you imagine if the opening sequence in Saving Private Ryan had been censored? Or if American Sniper cut away from the damage of Chris Kyle’s rifle shots? Gore doesn’t have to be 100% true to life––in the American Sniper script, a bullet is described as blowing the vertebrae out of an insurgent, a detail wisely discarded––but it’s beyond insulting to insinuate that war is something other than a massive loss of life.

One image I can never forget is in We Were Soldiers when a troop’s legs are so burned that the flesh slides off, exposing bone. Hard to watch, but the severity of napalm was seared into my brain.

The most memorable and impactful war films don’t shirk away from bloodshed. They place you right in the chaos, none of this shaky-cam nonsense where you can’t make out what’s happening and weapons don’t have any apparent effect on the human body. You experience the horror of violence with the characters, as it should be.

Another form of absurd censorship is the nitpicking of sound effects. Graphic gore is not always appropriate for the story, especially if it distracts from a scene’s emotion. In many instances, directors or writers will make stylistic choices on what not to show.

The suggestion of violence through audio can be even more horrific, such as William Wallace’s love, Murron, having her throat slit in Braveheart. The sound of the knife cutting flesh, the gurgles of her last breaths––it’s as disturbing as any spurting artery. Not a drop of blood is seen, but damn is it a powerful scene.

Audio can be a form of compromise without lessening impact, yet graphic sound effects like that will always earn an R-rating. Ludicrous.

Violence in superhero comics has recently drawn my attention. For decades, there was the Comics Code that had strict guidelines about controversial content in the medium. Now, the violence in mainstream Marvel comics often highlights the bodily damage sustained by superheroes, unlike their relatively clean movie counterparts. The Avengers can get by with a few scrapes in the movies but what they sustain in the comics is often shocking. Seeing your favorite hero take a serious beating is surreal and makes you think about the cost of their battles.

Violence in superhero comics has recently drawn my attention. For decades, there was the Comics Code that had strict guidelines about controversial content in the medium. Now, the violence in mainstream Marvel comics often highlights the bodily damage sustained by superheroes, unlike their relatively clean movie counterparts. The Avengers can get by with a few scrapes in the movies but what they sustain in the comics is often shocking. Seeing your favorite hero take a serious beating is surreal and makes you think about the cost of their battles.

For example, Spider-Man got absolutely decimated by Colossus in Avengers vs. X-Men. I’d never seen the happy, quipping Spidey so broken…but he never gave up. It was a harrowing––not gratuitous––moment. I love the Marvel films and am not suggesting they need to be more violent; it’s just an interesting disconnect from the evolution of the source material.

After reading this, you may think that I expect all entertainment to be spattered with blood. That’s not the case. As in my novel, it’s about picking your moments and hitting them with the proper oomph, not censoring difficult or controversial content for the sake of a wider audience. Violence should never be comfortable. Make the reader or viewer feel what your characters are enduring instead of being an impersonal, safe observer.

In Fall From Grace, the angels had never witnessed violence, war, or death. Thematically, there was no way I could gloss over the brutal impact of Heaven’s world war, not only on their bodies but their personal and cultural psyche.

Violence is a very unfortunate but primal, instinctual aspect of humanity and, as such, is an integral part of many stories. Fall From Grace doesn’t celebrate nor shy away from it by putting on a friendly sheen. If you’re going to make a movie or write a story with violence, then do it properly. Don’t insult the intelligence of your audience. Critics worry about the impact of violence on our society, but I worry about what people will do if they don’t understand the real consequences of it.

The world is full of darkness, and it’s the duty of art to explore it without compromise.

*Note – This essay is not addressing hyper-stylized violent works like 300 or the horror genre that are aimed at a specific audience as a form of escapism. I am a fan of those stories as well, but they reside outside of my arguments concerning more mainstream material.