Over the past few years, I’ve had many correspondences with fellow writer and cinephile, Sean P. Carlin. We agree on most fronts but have found ourselves on differing sides of one particular topic: the state of superheroes. I’m an unabashed fan of the Marvel and DC cinematic universes, seeing plenty of merit in the current direction of both. Sean, however, is far more critical of modern superhero stories and their media dominance. During the summer of 2016, when the genre made a bit less than its usual gobs of money and took some critical drubbings, we decided to break down our differing opinions in a good ol’ fashioned, respectful dialogue. Imagine that!

Part 1 – Innocence Lost, or Maturity Gained?

CARLIN: You and I have been engaged in a friendly debate these past few months over the merits of this so-called “renaissance” period in comic-book cinema––specifically, that you regard the proliferation of increasingly adult-themed superhero movies/stories as an evolution, whereas I see it, in many respects, as a violation (culturally speaking). I think I finally understand the disconnect in our perspectives: it’s a generation-gap thing. Superheroes were still pure when I was first introduced to them. Unburdened by psychological baggage, they existed to service what were very simple morality tales for their impressionable young audience. That is exclusively and unambiguously what they were meant to do, and that was what they were doing, very effectively, between 1940 and 1980 in comic books, TV shows, and even (on less frequent occasion) movies.

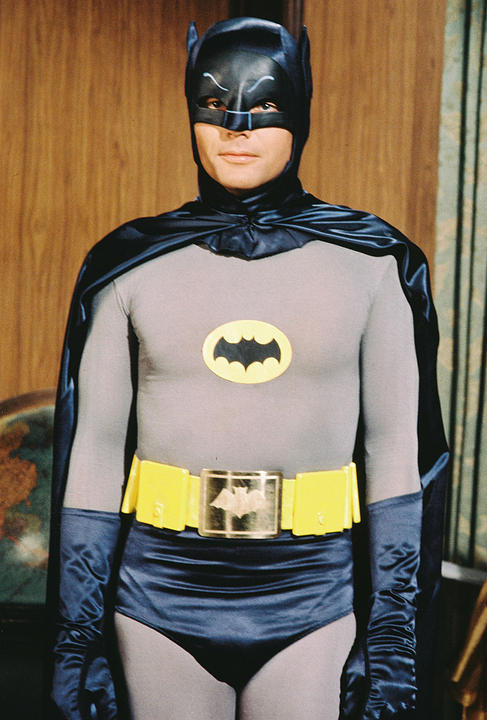

I consider myself exceptionally fortunate, because I became aware of superheroes during their last truly innocent phase. I was introduced to superheroes by way of syndicated afternoon reruns of the Adam West Batman series (itself a decade old at that point), and the long-running Super Friends cartoon. This is when superheroes were still licensed-property afterthoughts, not the tightly leashed, billion-dollar corporate assets they’ve become. They were still exclusively for children at that point; they hadn’t yet been coopted by a generation of adults. The bygone cultural ritual of Saturday-morning cartoons helped inform the rest of my superheroic education. Those were pretty chintzy, but we didn’t notice! We took it all seriously.

I consider myself exceptionally fortunate, because I became aware of superheroes during their last truly innocent phase. I was introduced to superheroes by way of syndicated afternoon reruns of the Adam West Batman series (itself a decade old at that point), and the long-running Super Friends cartoon. This is when superheroes were still licensed-property afterthoughts, not the tightly leashed, billion-dollar corporate assets they’ve become. They were still exclusively for children at that point; they hadn’t yet been coopted by a generation of adults. The bygone cultural ritual of Saturday-morning cartoons helped inform the rest of my superheroic education. Those were pretty chintzy, but we didn’t notice! We took it all seriously.

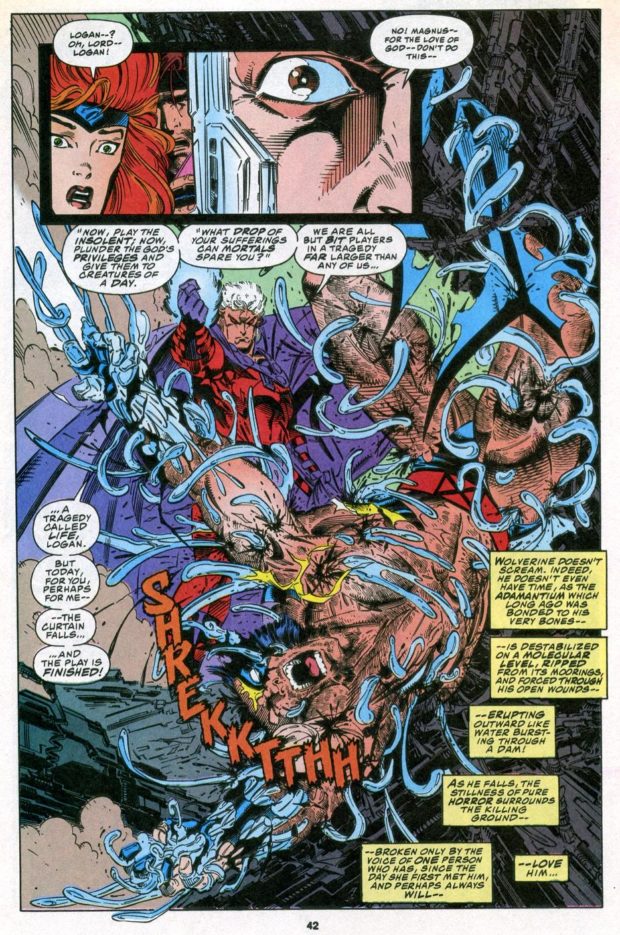

RITCHIE: Though we are only six years apart, those few years made quite a difference. Growing up, characters like Batman and Superman were already established icons, but I didn’t have emotional attachments to any particular portrayal. All I knew of Adam West were his parodied appearances on The Simpsons. The early ‘90s were my superhero heyday, and I was mainly a Marvel guy. The X-Men relaunch in 1991 (the #1 selling comic) and the 1992 animated TV series informed my lifelong love for the mutants. At that time, comics were becoming increasingly ambitious in their story arcs and bombastic art. The image of Magneto ripping the adamantium from Wolverine’s bones blew my young mind. Likewise, the animated series provided very accurate adaptations of classic Chris Claremont X-Men stories from the ‘80s that I was too young to read at the time. I was drawn to the deeper subtext of X-Men through stories about prejudice and civil rights––something I felt was lacking from other more jovial heroes. That was my Saturday morning cartoon. The X-Men played to my youthful sensibilities but also challenged me to ask more mature questions about life and morality. I felt elevated creatively and as a person, like (despite my age) I was experiencing something more than a typical cartoon or comic.

Innocence doesn’t have to come at the expense of depth. I’d much rather have children learn from these heroes, stories, and worlds than be a zombie sitting in front of the TV watching some candy-coated nonsense. Too often, the intelligence of children is marginalized. I’d argue that expanding their worldview through the themes of modern superhero films/shows/comics doesn’t have to be a loss of innocence. There’s a massive range of material out there, and the onus falls to the parents to find the most appropriate, engaging material.

Innocence doesn’t have to come at the expense of depth. I’d much rather have children learn from these heroes, stories, and worlds than be a zombie sitting in front of the TV watching some candy-coated nonsense. Too often, the intelligence of children is marginalized. I’d argue that expanding their worldview through the themes of modern superhero films/shows/comics doesn’t have to be a loss of innocence. There’s a massive range of material out there, and the onus falls to the parents to find the most appropriate, engaging material.

CARLIN: Funny enough, just as I was transitioning from my own last phase of innocence, Tim Burton’s Batman came out in 1989, when I was thirteen, between seventh and eighth grade. That was definitely the beginning of a new era for both superheroes and my particular interest in them. But it is worth noting that Batman started maturing considerably right around the same time I did, and that’s more than just my own subjective perception of him––that’s an objective fact.

RITCHIE: That’s evolution, and you can’t fight it. Tim Burton’s Batman was my first experience of seeing a superhero portrayed seriously in live action. Like the X-Men, the film’s gothic, dark style made me feel like I was partaking in a more “adult” story than how Batman was portrayed in the goofier Hanna-Barbera reruns. I became a fan of The Bat because the film wasn’t speaking down to me. But, like many people from my generation, Paul Dini’s Batman: The Animated Series became my go-to source for all things Gotham. It began airing in 1992 when I was ten, and I appreciated the stylized noir storytelling. It walked the line I mentioned above, not being a kiddie show but not too violent for my age group, either.

CARLIN: Then you had what I still consider to be the finest superhero story ever committed to celluloid, Richard Donner’s Superman: The Movie. Christopher Reeve really brought tremendous humanity and emotional vulnerability to the role of Superman––something my young mind definitely registered even if I couldn’t express what I was responding to––and he did it without sacrificing the character’s purer qualities or sense of joy. It’s an absolutely remarkable, magical performance. As much as Star Wars, those early Superman films really took hold of my imagination as a kid: they were epic and emotional and mythological, even. For my money, only Christopher Nolan has come close, in his own particular way, of achieving such profound emotional depth in a work of superhero cinema.

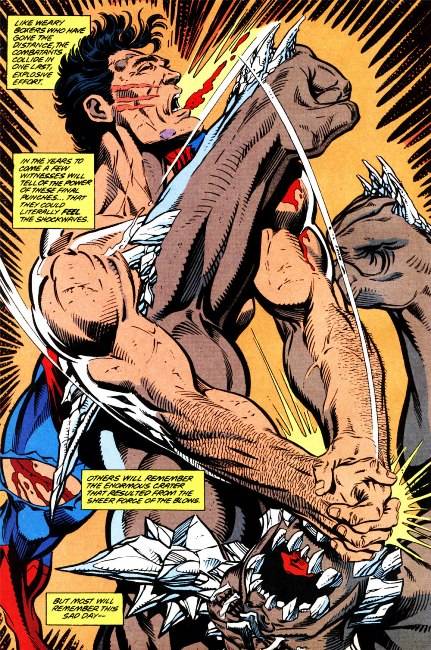

RITCHIE: Superman (1978) came out before I was born, and I didn’t see the film until my late ‘20s. Crazy, right? By not having that foundation of Christopher Reeve, my most memorable exposure to the character came from a completely different source: The Death of Superman. That mega story––a cultural event––molded my sensibilities of Superman into a more action-heavy, gritty (and yet still inspirational) hero. Real loss. Real tragedy. Real heroism. Donner and Reeve’s lighthearted, everyman approach is classic and spot-on for a certain era of Superman, but it doesn’t represent my era. My admiration for Superman was built upon a battle to the death followed by a high-concept, ambitious resurrection story. So you can understand why Henry Cavill’s more somber, physical Superman is right up my alley. Call it blasphemy, but Man of Steel was the live-action Superman story that I had always wanted to see.

RITCHIE: Superman (1978) came out before I was born, and I didn’t see the film until my late ‘20s. Crazy, right? By not having that foundation of Christopher Reeve, my most memorable exposure to the character came from a completely different source: The Death of Superman. That mega story––a cultural event––molded my sensibilities of Superman into a more action-heavy, gritty (and yet still inspirational) hero. Real loss. Real tragedy. Real heroism. Donner and Reeve’s lighthearted, everyman approach is classic and spot-on for a certain era of Superman, but it doesn’t represent my era. My admiration for Superman was built upon a battle to the death followed by a high-concept, ambitious resurrection story. So you can understand why Henry Cavill’s more somber, physical Superman is right up my alley. Call it blasphemy, but Man of Steel was the live-action Superman story that I had always wanted to see.

CARLIN: Wow! That’s staggering to me that you had no real sense, other than a vague awareness, of Adam West or Christopher Reeve. For me, they were the personification of arguably the two most recognizable superheroes. Even though neither actor was the first, or even the second, to play those parts, those were the definitive portrayals to my young mind––West less so now (though I appreciate his contributions immensely), but Reeve forever and always.

RITCHIE: “Definitive portrayal” is a perfect phrase for discussing superheroes. These characters are akin to Shakespearean icons like Hamlet in that actors from different generations have given their take, and (for better or worse) it’s never the same. Whatever portrayal speaks to you becomes ingrained in your psyche as the “definitive” version and will likely never be replaced. Kevin Conroy, who voices Batman in the animated series, was the character for me, just as Mark Hamill was my Joker. These two proved so influential that they continue to voice the characters to this day, as seen in the successful Arkham series of video games. And, of course, Harley Quinn was invented in the show…

I’m not sure anyone will ever be Wolverine to me other than Hugh Jackman*, or Iron Man other than Robert Downey Jr. The passion that those performances inspire in their fans…it lasts a lifetime. That’s special.

*Having seen Logan since this conversation, I can only hope that Dafne Keen continues to wield the claws. She’s the only Wolverine I can imagine at this point, heir apparent to the throne in her performance’s range and brutality.

Check back next Monday for Part 2 of the conversation!

I recently got the latest email message about the content on your website that I am happily subscribed to and will enjoy reading. I was attracted to this post after reading the details you mentioned about the piece you’ve written here in the message main body and I would express my interest in it keenly. I have read the article printed on this site and I really like it. It gives a very valid message that will possibly turn a few heads and I was given some awesome delight from it that made me really pleased to read it. It persuaded me to read on right to the end and I can reference the page so that I might come and read some more of the article and to read it over again a second time. Great to get the update. I completely get what you were trying to convey in the views expressed in the article.