Third person action/adventures may be my favorite type of video games. God of War and Uncharted are among my most beloved franchises. For me, there’s nothing more immersive than controlling a visible character (as opposed to first person) and exploring or slashing my way through a creative world. While some gamers play action titles to test their coordination via intricate battle mechanics, story has the premiere role in my overall experience. I need to connect with a character’s dramatic journey. DmC, a reboot of the Devil May Cry series, was reviled by many fans for its stark departure from the franchise roots. Recently rereleased as a technically upgraded “Definitive Edition,” the story of DmC remains largely untouched. The narrative is still not groundbreaking but was more than enough to keep me entertained for the duration of the game.

DmC takes place in Limbo City, a modern metropolis where “terrorists” known as The Order have been vilified in the media. A power-hungry banker named Kyle Ryder controls the city, and much of the world, through the power of debt. Ryder is actually an ancient demon named Mundus who has enslaved humanity from the shadows, and only one person can stop him––son of the legendary demon Sparda.

DmC takes place in Limbo City, a modern metropolis where “terrorists” known as The Order have been vilified in the media. A power-hungry banker named Kyle Ryder controls the city, and much of the world, through the power of debt. Ryder is actually an ancient demon named Mundus who has enslaved humanity from the shadows, and only one person can stop him––son of the legendary demon Sparda.

The player assumes control of Dante, a sword and dual-pistol wielding badass degenerate. He has no memory of his childhood or any desire to contribute to the greater good outside of killing any demons that get in his way. The game opens with a Hunter Demon finding Dante living near a shoddy carnival and pulls him into Limbo, a demonic realm that exists side-by-side with the real world.

Kat, a human capable of wandering Limbo in spirit form, helps Dante and brings him to The Order. Not terrorists at all, The Order is actually trying to save the world from Mundus. Their leader is Vergil, Dante’s twin brother. Vergil helps restore Dante’s memory, and we learn that the brothers are Nephilim: sons of a demon (Sparda) and an angel (Eva). Nephilim are stronger than both species and the only beings capable of defeating Mundus.

Kat, a human capable of wandering Limbo in spirit form, helps Dante and brings him to The Order. Not terrorists at all, The Order is actually trying to save the world from Mundus. Their leader is Vergil, Dante’s twin brother. Vergil helps restore Dante’s memory, and we learn that the brothers are Nephilim: sons of a demon (Sparda) and an angel (Eva). Nephilim are stronger than both species and the only beings capable of defeating Mundus.

The story is a simple but structurally sound tale of two brothers reuniting to fight a common enemy only to clash over stark differences in their methods. It follows a traditional 3-act structure complete with a hero setting out on his journey, a midpoint twist, and an all-is-lost moment at the end of act 2. Gamers may not recognize the 3-act structure, but it has been burned into their subconscious from most movies. It is accessible and safe storytelling that acts as a crutch of sorts for the reboot’s more controversial changes.

I actually had a pitch meeting for the Devil May Cry movie adaptation years ago when DmC was still in development and saw the story’s promise in the early notes. However, the final execution of the narrative is somewhat bland. The player fights a wave of enemies then watches a cutscene––rinse and repeat. It’s not the most elegant or innovative form of storytelling. I would have liked a little more exploration and adventure, but it’s clear that action is the focus of DmC.

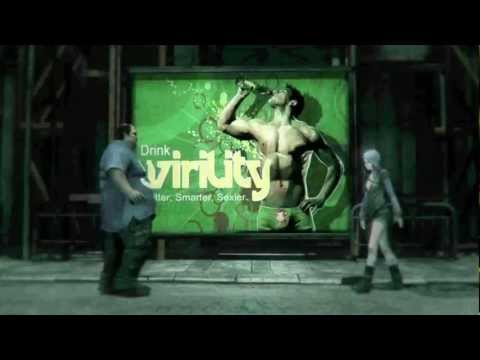

From a storytelling perspective, what I found most interesting about DmC was the social satire…even if it’s far from subtle. Mundus’ plan for enslaving humanity is a stylized critique on Western culture. “Virility,” the most popular soft drink in the world, is touted as increasing sexual performance while decreasing weight loss. Sound too good to be true? It’s really a demonic concoction that essentially lobotomizes the consumer, making them docile and unquestioning.

From a storytelling perspective, what I found most interesting about DmC was the social satire…even if it’s far from subtle. Mundus’ plan for enslaving humanity is a stylized critique on Western culture. “Virility,” the most popular soft drink in the world, is touted as increasing sexual performance while decreasing weight loss. Sound too good to be true? It’s really a demonic concoction that essentially lobotomizes the consumer, making them docile and unquestioning.

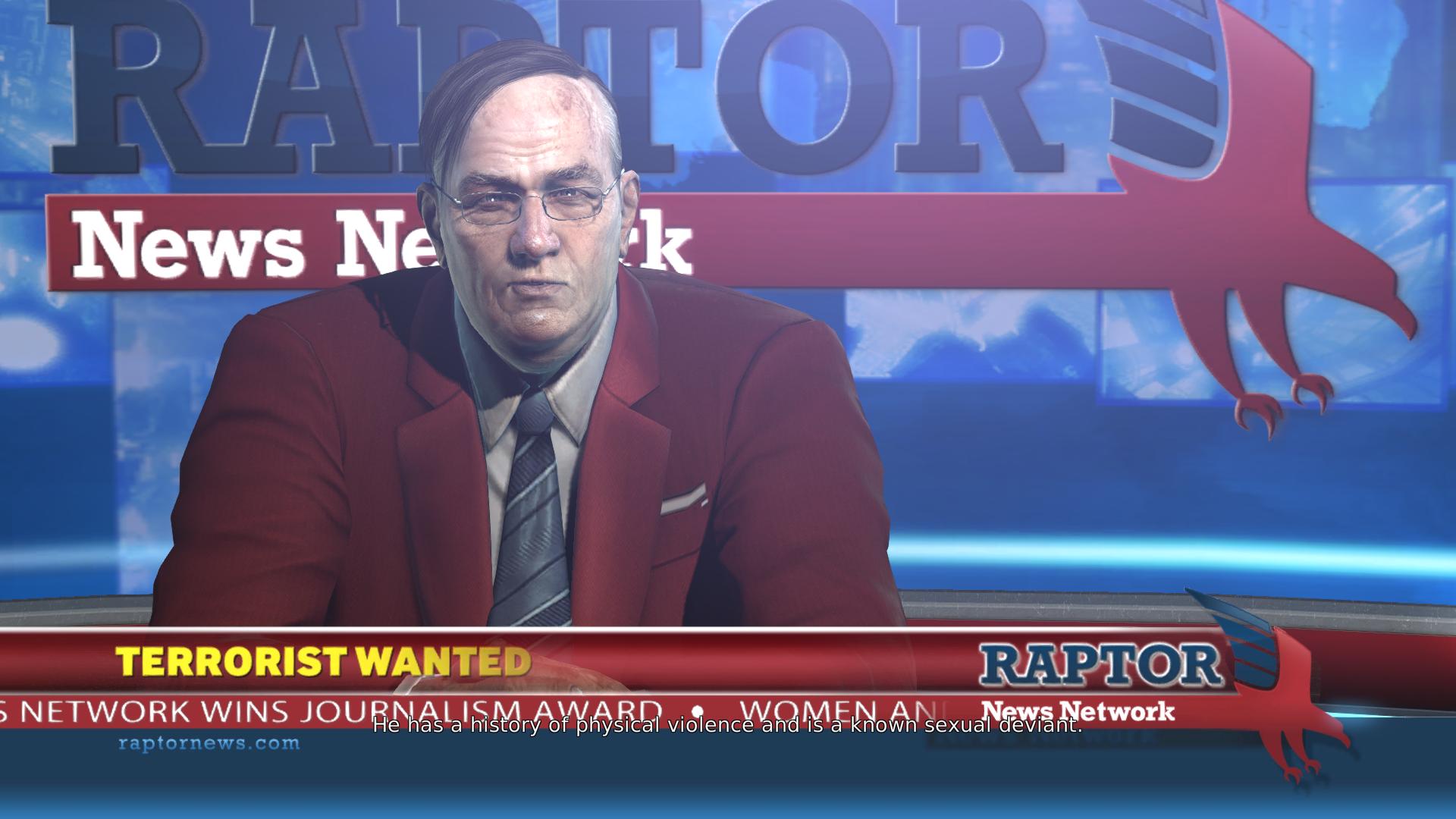

The Raptor News Network that controls the media is a parody of Fox News, headed up by demon Bob Barbas who is “just doing God’s work.” It’s very intriguing that Mundus chose to take over the world not through grand gestures of power but through political subterfuge, wealth, product placement, and media propaganda. Demons are everywhere, but the populace is ignorant to their schemes.

The Raptor News Network that controls the media is a parody of Fox News, headed up by demon Bob Barbas who is “just doing God’s work.” It’s very intriguing that Mundus chose to take over the world not through grand gestures of power but through political subterfuge, wealth, product placement, and media propaganda. Demons are everywhere, but the populace is ignorant to their schemes.

Developers Ninja Theory Westernized the Devil May Cry franchise in an attempt to ground Dante more and appeal to American audiences. To be fair, the previous entries had convoluted storylines (by American standards) that were never the highlight of the games, but an amazing sense of style and fun always persisted. In DmC, the gothic vibe has been traded for modern grittiness, seen everywhere from the characters to the level design. This has been one of the largest criticisms for the game––it doesn’t “feel” like Devil May Cry. In fact, the DmC version of Dante was so disliked by the hardcore fanbase that he earned an Internet name of Donte to fit his supposedly emo vibe.

Story in action-heavy games can be tricky. I love to take a break and watch cutscenes, but many action gamers just want to get to the next battle. The gameplay of DmC moves at a wicked pace, and the story has to merge with that, sacrificing character development. There’s a lot of rushed exposition that could have been incorporated in a more interactive fashion. By trying to walk the line between story and action, DmC doesn’t fully satisfy either extreme. Even with the edgy, violent, modern feel of DmC, the story ultimately comes off feeling restrained and occasionally neglected.

Story in action-heavy games can be tricky. I love to take a break and watch cutscenes, but many action gamers just want to get to the next battle. The gameplay of DmC moves at a wicked pace, and the story has to merge with that, sacrificing character development. There’s a lot of rushed exposition that could have been incorporated in a more interactive fashion. By trying to walk the line between story and action, DmC doesn’t fully satisfy either extreme. Even with the edgy, violent, modern feel of DmC, the story ultimately comes off feeling restrained and occasionally neglected.

DmC is not the best (or worst) game in the franchise, and it certainly doesn’t deserve the hatred spewed at it from fans. The simple but engaging tale of two brothers hits a primal, relatable chord that is only somewhat out of tune. Unfortunately, it seems like DmC is the beginning and end of the reboot as Ninja Theory is done with the franchise. The Westernization experiment ultimately didn’t connect with the core fans of the series. Then again, gamers are notoriously bitchy and adverse to change. I dig the game, but you can’t please everyone.